- Home

- Stephanie J. Blake

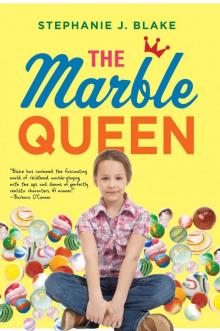

The Marble Queen

The Marble Queen Read online

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2012 by Stephanie J. Blake

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to:

Amazon Publishing

Attn: Amazon Children’s Publishing

P.O. Box 400818

Las Vegas, NV 89140

www.amazon.com/amazonchildrenspublishing

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blake, Stephanie (Stephanie J.), 1969-

The Marble queen / by Stephanie J. Blake. -- 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Freedom Jane McKenzie does not like following rules, especially about what girls should do, but what she wants most of all is to enter and win the marble competition at the Autumn Jubilee to prove herself worthy of the title, Marble Queen.

ISBN 978-0-7614-6227-9 (hardcover) -- ISBN 978-0-7614-6228-6 (ebook)

[1. Family life--Idaho--Fiction. 2. Sex role--Fiction. 3. Marbles (Game)--Fiction. 4. Contests--Fiction. 5. Idaho--History--20th century--Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.B56513Mar 2012

[Fic]--dc23

2011040132

Book design by Becky Terhune

Editor: Robin Benjamin

First edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Sam—

for always

Contents

Last Will and Testimony

Chapter One Taking a Stand

Chapter Two Higgie and the Worm

Chapter Three Mama’s Rules

Chapter Four Daniel Calls Quitsies

Chapter Five The Big Zucchini

Chapter Six Mama and Daddy’s Kitchen Debate

Chapter Seven A Neighborly Chat

Chapter Eight Gone Fishing

Chapter Nine Black Sunday

Chapter Ten School Daze

Chapter Eleven Breaking Pearls

Chapter Twelve Spitting Rocks

Chapter Thirteen Swallowing Marbles

Chapter Fourteen Winner Takes All

Chapter Fifteen A Spooky Night

Chapter Sixteen A Meeting of Minds

Chapter Seventeen How You Play the Game

Chapter Eighteen Oh, Baby!

About the Author

July 29, 1959

The Last Will and Testimony of

Freedom Jane McKenzie,

of 121 Lilac Street, Idaho Falls, Idaho

If I die before I wake, my marble bag is for Daniel Coyle to take. Except for the light brown aggie. He knows which one. That marble’s for my other friend, Nancy Brown. I promised to give it to her because I accidentally broke her ballerina music box last week, and now it has to be glued so her grandma won’t know it was broken.

Signed,

Freedom Jane McKenzie

P.S. Daniel CANNOT have the blue taw, either.

No matter what he says, it’s for Higgie.

P.P.S. I mean it!!!

Chapter One

Taking a Stand

AUGUST 3, 1959

My mama, Mrs. Wilhelmina Anne McKenzie, was cutting up a chicken. And thinking back on it, I shouldn’t have bothered her at all. Sometimes my mouth goes off, and I can’t help myself. You know how you’ll ask your mama about something, and she doesn’t say anything for a whole minute, so you think she didn’t hear what you said? Then when you ask for that something again, she starts hollering? Well, it happens at my house almost every other day, and I’m sure tired of it.

It was a regular summer afternoon. All of the windows in our house were wide-open, and I could hear the big boys playing stickball in the street. A heat wave rolled in through the ripped screen on the back door and swirled around the kitchen, from the brown speckled linoleum on up. Mrs. Zierk was plunking away on her piano next door. My annoying little brother, Higginbotham (Higgie for short), was sitting on the metal step stool in the corner, having a snack before supper, pretending he was invisible under the raggedy blue blanket that covered his dirty blond head.

Higgie always thinks he’s invisible. His giggling was getting me riled. Instead of eating the peanut butter and honey sandwich, he was throwing pieces of it on the floor. Mama doesn’t like it when we waste food, but she was too busy with supper to care. Even though Higgie’s four, he acts like a dumb bunny most of the time.

All I said to Mama was that I needed a shiny new pair of roller skates because I’d lost the key to mine. Also, the wheel on the right one is kind of squeaky, on account of my leaving them out in the rain overnight. I scratched at a swollen bug bite on my leg while I waited for her answer.

A few minutes later, Mama still hadn’t given me an answer about the roller skates. I noticed how round her baby belly was getting. I’m going to have a new brother or sister this fall. I’ve made my peace with it, but Mama hasn’t.

She threw four thick chicken pieces into the black skillet, where they crackled and popped and practically danced in the grease. The smell of that fried chicken tickled my nose. My tummy growled with hunger. After she turned down the flame and put the lid on top, I tugged on her pin-striped apron. “Mama. Did you hear me? I really, really need some new roller skates.”

I guess she’d heard me just fine, because she slammed a bowl of mashed potatoes down on the table and said, “You just had a birthday!”

It’s true. I turned ten last week and got lots of neat presents. Aunt Janie and Uncle Mort gave me a little red diary. So far I’ve written my “Last Will and Testimony” in it. Nancy gave me a pink Hula-Hoop, and Daniel gave me a paint-by-numbers set. Mama and Daddy got me a Barbie doll.

Sure, Barbie is pretty and all. But I’ve only got the black zebra-striped bathing suit she came in. She’s got teeny tiny shoes and gold earrings, and I’m afraid I’ll lose everything. Mama was so proud when I unwrapped it. The doll cost a whole three dollars. I suppose I’m lucky to have it.

I guess I should’ve told Mama ahead of time that I wanted a brand-new pair of skates instead. We got my old skates at the church rummage sale for a nickel. They never really worked from the get-go, unless I’m on a steep hill. The only hill that’s good for skating down is the one by Tautphaus Park, by the waterfalls, and I’m not allowed to go near Snake River by myself on account of that “terrible incident” last summer.

I could tell I’d upset Mama. She almost never wants to buy anything new. Her family was so poor she half grew up in an orphanage, although her parents lived in the next town over. It was the Depression, so a lot of people had hard times. Mama lived there for three years before her daddy came to collect her one day as if nothing had happened.

And now she’s having another baby. But that shouldn’t mean I can’t get a Barbie and a new pair of roller skates, so I explained this ever so nicely. Mama sighed and brushed my hair out of my eyes before going back to the stove, where she complained about the lumps in the gravy.

She flicked a fly from her cheek and whispered, “You aren’t getting anything new until Christmas.”

“Christmas is four months away,” I said. “I’d like to do some more roller skating before the summer is over.”

Higgie giggled under his blanket. “Christmas!” he yelled. Then he pulled the blanket off his head and shoved his sandwich into his pink mouth. He chewed a bit and opened up wide, showing me the mess inside.

“You are disgusting,” I told him. He pulled the blanket back over his head.

Mama

simmered along with the gravy. Her wavy black hair was pinned up on account of the hot weather. Beads of sweat dotted her forehead. Mama had given up on her lipstick. Usually she’s got on a thick red coating morning, noon, and night.

She banged the wooden spoon on the edge of the pot. “For heaven’s sake! It’s been one thing after another with you this summer. Freedom Jane McKenzie, find something you are good at and stick with it!”

How am I supposed to know what I’m good at until I’ve tried everything?

I put my finger up in the air and declared, “Mama, I am good at something. I’m good at shooting marbles.”

She handed me a stack of white dinner plates. “Marbles are for boys. Set the table.”

Higgie popped his head out and said “Christmas” again.

“Hush!” I said to my brother. “But, Mama—”

“Not another word about it, Freedom!”

I hung my head. When Mama went to get the rolls from the oven, I poked my brother. His precious blanket fell on the floor. I stepped on it. That shut him up, except for the whimpering. He’s such a baby. He put his fingers in his mouth, and as I went to poke him in the stomach, Mama caught me.

“Freedom!” She pointed to the bathroom. “Get yourself in there and wash your hands. I swear! Your hands are the grubbiest things I have ever seen.”

I looked at my hands. I had a callus on my right thumb from shooting marbles all summer. I examined my nails. Black dirt was crammed up under each and every fingernail.

Mama narrowed her dark brown eyes and stared at my scrawny legs. I didn’t dare look down, but I knew that my shins were probably filthy from kneeling in the dirt all afternoon with the boys at the ring. I’d played four games and won all of them.

I hoped Mama wouldn’t notice the hole in my second-to-best yellow dress, where Daniel had pulled off the daisy pocket. He’d already won a cat’s-eye and two aggies from me, and when I wouldn’t give up a third aggie, he tried to wrestle me for it, ripping my pocket. I’d shoved him as hard as I could, yelling, “You can’t wrestle a girl in a dress, Daniel Coyle.”

He told me to go jump off a bridge!

Daniel lives across the street. We used to do everything together. Fun things like digging for fishing worms, skipping rocks at the pond, hunting for grasshoppers, and practicing yo-yo tricks. He’s usually at our house more often than his own. He’s been my best friend ever since I was in kindergarten and he was in first grade, but lately he’s been acting kind of mean. The other day in the candy aisle at the drugstore, Daniel told me not to stand so close. He didn’t want people to get the wrong idea. Whatever that means.

Of course, Mama notices everything. She snapped, “And what have you done to your dress?” as she followed me out of the kitchen. I skedaddled sideways before she could thump me with her spoon.

Daddy rustled his newspaper from the couch. “Now, Willie, leave the girl alone.”

Seems my daddy, Homer Higginbotham McKenzie, is always saving me from Mama. I put my arms around his neck. He was still wearing his green work overalls and smelled of Schaefer beer and WD-40, with a hint of Old Spice. He might have been at work all day, but the ducktail part in the back of his hair was still perfect.

“That chicken sure smells delicious, Willie,” he added. He gave Mama one of his big winks, and she stomped back into the kitchen.

I’ll be starting fifth grade soon, and Mama has been going on and on all summer about what girls can and can’t do. I never agree with her. Never. What’s the matter with a girl shooting marbles? I’m talented. Daddy said so. He’s the one who gave me the marbles in the first place.

In fact, almost all of the best marbles in my pouch were Daddy’s when he was a young mibster. That’s what you call a marble player, a mibster. And I’m one of them. Well, I am when the boys in the neighborhood let me play.

Daddy taught me everything I know about marbles.

He also gave me my unusual name. “Freedom is a good, strong name for a good, strong girl,” he says. He also calls me Sugar Beet, but I’m trying to break him of it. My name fits me just fine, even though Mama didn’t get to pick it out. She wanted to name me Ellen, after her dead mama, or Jane, after Daddy’s sister; but Daddy argued that Jane makes a better middle name.

Mama says calling a girl Freedom is just borrowing trouble.

She doesn’t know everything, though. For instance, when Aunt Janie gave me a pair of stiff dark blue jeans for Christmas last year, Mama said I couldn’t roll them up because it showed off too much ankle. I wear dresses all the time, showing off my knobby knees, so I asked, “What’s the difference between rolled-up jeans and dresses with bare legs and bobby socks? You can see my ankles either way.”

Mama just said, “Don’t get fresh, Freedom. You won’t see Mrs. Kennedy wearing jeans.”

It’s always Mrs. Kennedy this and Mrs. Kennedy that. Mama claims I’ll lose interest in marbles one day and be on to something else. I swear, I’m going to prove her wrong.

Daddy held up a page of the newspaper. “Look here, Freedom. They’ve announced the date of the competition.” He read the words aloud: “‘Twelfth Annual Marble-Shooting Competition to be held November fourteenth during the Autumn Jubilee. For ages ten and up. Sponsored by the Post Register. Entry fee: two dollars.’”

I jumped up and down. “I’m finally old enough to enter!”

Mama yelled from the kitchen, “We’ll have to see about that!”

“And the prize is a hundred dollars!” I yelled back.

Daddy chuckled. “You can cut out the announcement after supper.” He patted my arm. “Hurry now, Sugar Beet. Get cleaned up. I’m starving. And your mama is going to have a fit if supper gets cold.”

I scrubbed extra hard with that slimy, red bar of Lifebuoy soap. I even rubbed my elbows and knees with a washrag until they stung. I thought about brushing out my stringy brown hair, but the knots were too big. Mama always complains about my sensitive scalp. I wish she wouldn’t pull so fast with her poky hairbrush. She also says my hair wouldn’t be such a mess if I’d stop “gallivanting around like a wild horse.”

I counted three new freckles in the bathroom mirror and decided it was time to take a stand. Everyone knows that girls are just as good as boys. Least that’s what Daddy tells me. After I hung up the pink hand towel—nice and straight, the way Mama does—I came out to the kitchen and put my hands on my hips real important-like to make my announcement:

“I’m old enough to enter the marble competition this year. I’ve decided I’m going to be the next Marble King of Idaho Falls. You’ll see.”

Mama set down the platter of fried chicken on the table and pointed to my chair. “Sit, Marble King. Supper’s getting cold.” She tied a napkin around Higgie’s neck. Then she went on, “I don’t believe a young lady should be playing marbles with boys, especially against them. And furthermore—”

Daddy cut her off. “Let’s say grace. I’m dying here.” He put a chicken leg on my plate and grinned. Sometimes he looks exactly like Elvis.

Mama sighed. “I’ll think about the competition, Freedom.”

“Thank you, Mama.”

After that it was kind of peaceful during our meal until Higgie said, “You can’t be a king. Only boys can be kings.”

“Fine, I’ll be the Marble Queen then.”

“You can’t be a queen, neither,” Higgie argued. “Queens are old.”

He stuck out his tongue and rolled his eyes all the way back into his head. All I could see were the white parts of his eyeballs. So I pinched him on the arm as Mama ladled fresh gravy onto Daddy’s mound of mashed potatoes.

Now here I am in my room. So what if Mama sent me to bed when it’s still light out? I didn’t want that juicy chicken leg anyhow. I’m sure she threw the newspaper away, too.

But Mama had to do the dishes all by herself. So there.

Chapter Two

Higgie and the Worm

AUGUST 7, 1959

This morning Higgi

e and I had to go downtown with Mama so I could get some new shoes for school. All I know is that bringing Higgie along was a mistake. I tried to stay in step with Mama, but her heels were clicking on the pavement, and her black pocketbook was whipping against her side. Higgie galloped ahead. Mama was in a hurry because she had a doctor’s appointment, and after that she still needed to finish cleaning up the house and bake a pie.

We passed the bank, the jeweler, and the drugstore. The street was nearly empty. A few cars were parked here and there. A man sat on a bench eating an ice cream cone. A stray cat streaked by. Higgie tried to take off after it.

Mama grabbed his collar just in time. “Higginbotham!”

Whenever Higgie comes shoe shopping with me and Mama, I never get a lollipop from the man who measures our feet.

Last time we got new shoes, Higgie squashed my toe with his dumb old stick pony. I cried, and Mama had to buy the saddle shoes that I was trying on because one got all scuffed up. I had wanted the penny loafers. The time before that, Higgie was leaning over in a chair and fell backward. He knocked over a display of shoe polish. Mama paid for five jars, even though we didn’t get to take them home. I’ll never forget the way the man’s face got all scrunched up as he threw the broken jars into the trash can.

Right before she opened the door to the shoe shop, Mama tweaked Higgie’s ear and told us, “If either of you makes a scene today, I’ll take you out to the car.”

I’m not sure why I was getting a lecture.

This time Higgie had already started trouble by getting his thumb caught in the car door in the parking lot. It’s not my fault he wasn’t out all the way before I slammed the door. Mama had said we needed to hurry. His thumb wasn’t even bleeding, but Mama had wrapped her hankie around his hand and kissed Higgie’s tears away, saying, “You’ll be fine.”

He kept repeating “My thumb is beeping” the whole time I was trying on shoes.

Finally, I got a pair of black penny loafers and a purple lollipop. Higgie got a red lollipop. I planned on asking Daddy for two pennies to put in the pockets of the shoes. When the marble competition comes around, I’ll have at least two pennies toward the entry fee. That’s if Mama lets me compete. I’m not sure why she’s got to think about it so long, but I’m going to get Daddy to make her agree—somehow.

The Marble Queen

The Marble Queen